Sexualised wartime violence

Sexualised violence against women and girls during wars has always been a part of human history. It occurs every day, all over the world. The predominantly male perpetrators include soldiers, paramilitaries and police officers, but also civilians. In a series of resolutions and accords, the international community has pledged to protect women from violence and strengthen their rights. However, the political will is still lacking to actually fulfil these promises and implement the agreements. Unless we manage to eradicate the misogynist structures underlying sexualised violence and create gender justice in their place, women and girls will not be able to live in dignity and free of violence.

Facts and figures on sexualised wartime violence

What forms does this sexualised violence take?

Sexualised violence has many forms. Common to them all is that sexual conduct and touch occurs without the other person’s approval or consent, or their ability to grant consent. So it is a crime against the right of sexual self-determination of that person. This violence encompasses: sexual insults, unallowed touching of parts of the body, unwanted showing and sending of sexual and pornographic images, forced participation in sexual and pornographic activity, rape, sexual torture, female genital cutting, sexual exploitation, sexual enslavement, forced prostitution, forced pregnancy, forced sterilisation, forced abortion, intentional infection with sexually transmitted diseases such as AIDS.

What are the causes of sexualised wartime violence?

During times of war, all of the forms of discrimination that exist during peacetime continue in a more severe way. This includes the disadvantaging and sexist denigration of women. In most countries, their rights and needs are deemed less important than those of men and boys. Various forms of gender-based of violence are simply part of everyday life for many women, often combined with further types of discrimination such as racism or homophobia. They are part of the prevailing patriarchal power structures. Sexualised violence becomes established in times of peace, is exacerbated during armed conflict, and propagates in post-war societies. The use of rape as a strategic means to conduct a war is, in the end, a ‘logical’ consequence of these unequal power relationships. Even if sexualised violence during conflicts is used against men, this is usually still conducted by men and it is still an expression of patriarchy’s dominance behaviour.

The continuum of sexualised violence

“[...] Even before war breaks out, sexualised violence or the threat of it is an everyday experience for many women and girls. [...] Then there are the sexist and misogynist attitudes of a range of severity, securely anchored in socio-cultural practices, societal norms, and military training – none of which allow even the seed of an awareness for the injustices to form. [...]” Tip: You can find the article “Sexualised Wartime Violence – Perception and Consequences” by Gabriela Mischkowski and Monika Hauser in full in our Specialist Brochure (p. 8).

What function does sexualised violence have during a war?

Patriarchal societies assume that there are only two genders: male and female. Heterosexuality is the norm. Masculinity is associated with dominance, strength and power; femininity with passivity, meekness and sexual abstinence. During a war, men more clearly reveal their claims of possession over the supposedly weaker sex. The rape of women and girls – and, for example, homosexuals or transgender (LGBTIQ) people – also serves to reassure them of their own male superiority. It is a symbol of humiliation of the opponent, who cannot protect ‘his’ women. As a strategic weapon of war, sexualised violence is also deployed as part of ethnically motivated expulsions or murders. Sexualised wartime violence is also a means of political suppression. In general, it is used with the aim of demoralising the opponent, defeating them emotionally, dividing them or humiliating them. Survivors are isolated and stigmatised.

Who are the perpetrators of sexualised wartime violence?

Perpetrators can be found on all sides of the conflict. The generally male perpetrators include soldiers, paramilitaries and police officers, but also civilians. Sexualised wartime violence is usually carried out by men. Rapes are tolerated and sometimes encouraged by commanders, and orders to rape can form part of a military strategy.

Who are the victims of sexualised wartime violence?

The victims of sexualised wartime violence are generally women and girls. They belong to all parties to the conflict and come from every social class and ethnic group. People with LGBTIQ identities, such as homosexuals or transgender people, also have a higher risk of suffering sexualised violence. During war men also rape boys and other men. In this case, their rape is an act of symbolic and physical ‘emasculation’. Taking a woman as a symbol of another religious, cultural, national or ethnic group and raping her is done with the intention of demonstrating superiority over that whole group. From the point of view of the enemy, the victim is a lesser being in multiple aspects.

Are there any statistics about sexualised wartime violence in Germany and Europe?

In general, figures on sexualised wartime violence are difficult to determine. Many of those affected do not speak out because of shame or fear of stigmatisation and exclusion, or the renewed pain of remembering traumatic experiences. Others died from the consequences of their rape, were murdered, or took their own life years later. Wartime rapes are rarely recorded or documented systematically, so it can be assumed there is a high number of unrecorded cases. Example World War II: Witness reports, memories of former soldiers, hospital and military files, as well as clergical records all offer indications of the immense extent of the rapes. According to academic estimates, millions of women and girls were raped. The UN Commission investigating violations of international humanitarian law estimated the number of women who were raped during the Bosnian War (1992-1995) at 20,000.

Are there statistics on sexualised wartime violence around the world?

It was not until the Balkan wars that sexualised wartime violence gained significant international political attention. In a series of resolutions and declarations, the international community pledged to protect women from violence and to strengthen their rights. In 2008, the UN Security Council passed Resolution 1820, declaring rape and other forms of sexualised violence to be war crimes. One of the measures it called for from UN member states was to record crimes of sexual violence during and after armed conflicts. However, it is still the case that sexualised wartime violence is a taboo issue in many societies, and the number of unreported cases remains high. At the governmental level there is a lack of systematic structures, staffing and financial resources needed to record sexualised wartime violence. The Office of the UN Special Representative on Sexual Violence in Conflict publishes an annual report on progress in implementation of the resolutions.

What consequences does the violence have for the women affected?

Physical consequences of violence include infertility, incontinence and psychosomatic disorders such as chronic abdominal pains. For many women and girls, consequences are also an unwanted pregnancy or infection with HIV. Psychological disorders such as extreme anxiety or depression are frequent. Research suggests that 50 to 60 per cent of those affected develop a post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Frequently, rapes are ignored or trivialised, and often they are even twisted into an accusation that the woman behaved inappropriately. In very patriarchal societies, women who have been raped are deemed to have committed adultery, often leading to their imprisonment and/or ostracisation from families or communities. Many even have to fear for their lives. And on top of this, it then becomes almost impossible for them to secure their livelihood and that of their children.

What consequences does the violence have for the families of those affected?

Sexualised violence disrupts family cohesion. For example, people affected by rape often find it difficult to permit emotional intimacy with people close to them. More than one half of the participants in a study on the long-term consequences of sexualised wartime violence carried out by medica mondiale and Medica Zenica reported that their experiences of rape have an absolute or partial influence on the relationships to their children. Some told of the great difficulties they experience in being an emotionally stable parent. Symptoms of trauma, if left unprocessed, can be transmitted within a family and on to the next generations, in the form of excessive irritability or separation anxiety, for example. In post-war societies, the crimes are suppressed and swept under the carpet. Many of those affected keep silent out of shame or fear of stigmatisation and ostracism.

What consequences does this wartime violence against women have for society?

Sexualised wartime violence is not a purely individual fate for the person affected: it has long-term effects on the whole social environment. Deployed in a targeted manner, the attacks are designed to terrorise and humiliate the other side, in order to destroy social cohesion and demonstrate the power of the attackers. The impacts of sexualised wartime violence also reach further, as transgenerational trauma, into the next generations, causing both psychological disorders and very high economic costs. In many countries there is barely an awareness of the injustice suffered by these women, or of the need for sexualised violence against women to be a punishable offence. Survivors continue to be stigmatised and excluded. The perpetrators generally escape with impunity and there is very rarely a systematic process to come to terms with these crimes. Furthermore, although the consequences of violence are predominantly borne by the women, they are rarely involved in peace processes.

What consequences does this wartime violence against women have for the state and the economy?

Sexualised wartime violence is a war crime and human rights violation that inflicts immeasurable damage on every human society. Numerous fundamental liberties, rights and human dignity are violated by sexualised wartime violence. It seems to be the case that governments accept this and even grant their tacit approval. The deterioration in the life conditions of those affected, both directly and indirectly, lasts a long time. Those with political responsibility are failing to satisfactorily fulfil their duty to acknowledge and prosecute these crimes. The economic costs of wartime violence against women and the transgenerational consequences that result from this are immense. They can even be calculated as running into the billions or trillions of dollars. These include, for example, direct costs of medical emergency provision and subsequent treatment, psychosocial therapies and counselling, investigations by police and courts, as well as the costs of society coming to terms with this. Additionally, many of those affected by sexualised violence are unable to work for a long time and are dependent on welfare from their community or society. Society and the economy also cannot benefit from their skills and individual qualifications, or their labour.

What opportunities are there for state intervention?

Sexualised wartime violence is a breach of international law. Governments are obliged to punish this crime. Wartime rape can be taken to the International Criminal Court (ICC) as a war crime and also a crime against humanity. An effective prosecution of these crimes is necessary if those affected are to experience justice and redress, such as compensation payments. Another important factor for survivors trying to come to terms with their experiences is an official acknowledgement, made publicly, that these rapes are an injustice that should not be tolerated by society. Many countries now have political initiatives set up to prevent and prosecute sexualised wartime violence. However, there is still insufficient political will or widespread public awareness for the necessity of violence prevention and the significance of short- and long-term assistance for those affected. This support is essential if we are to avoid passing on the consequences of this violence to the next generations in the form of transgenerational traumatisation.

What is the international community doing to eliminate sexualised wartime violence?

In a series of resolutions and declarations, the international community has pledged to protect women from violence and strengthen their rights. The CEDAW convention, passed by the UN in 1979, obliges the signatory states to ensure legal and real equality for women in all areas of life, and to eliminate discrimination against them. With Resolution 1325 on “Women, Peace and Security”, the United Nations Security Council concluded that a contribution to world peace can be made by protecting women and girls, and also by their participation in peace negotiations. This Resolution means that since October 2000, UN member states are obliged to protect women and girls from sexualised violence during armed conflict and in the post-war period, and to ensure their equal participation in peace processes and reconstruction. The International Court of Justice (ICC) is responsible for the punishment of genocide, severe war crimes and crimes against humanity, which include wartime rape.

What can society do to support those affected?

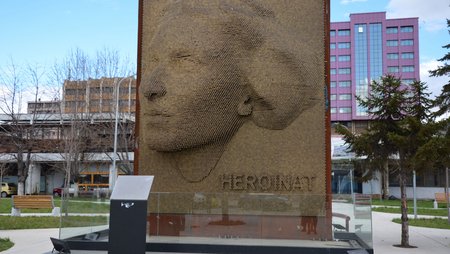

In order for survivors to deal with the violence they experienced, it is essential for them to receive acknowledgement that they suffered an injustice, to have material and physical security, and to be accepted (back) into a community showing them solidarity. Their trauma is not only theirs as individuals but also a trauma of their society. An awareness of this fact can make a decisive contribution to removing the taboos and stigma surrounding the issue of wartime rape. In order to overcome the culture of silence, we need statements of position from authorities and public figures, an active culture of remembrance, and the inclusion of the issue in schoolbooks and history books.

In action for women’s rights and against violence: Examples of our work worldwide

Public awareness work on violence against women and integrated support for survivors

In order to make people in everyday situations aware of how to deal with women who have been affected by violence, medica mondiale and its partner organisations conduct training in trauma-sensitive and empowering ways of working for staff in police forces, hospitals, schools and religious institutions. The organisation's own project workers also receive ongoing training.

Our partner organisation medica Liberia has built up a broad protection and assistance network in rural areas to support women and ensure their rights are respected. In village communities, women and girls affected by sexualised violence can seek out specially trained counsellors. Men are also involved in the protection networks in order to ensure long-term, sustainable change in the communities. A referral system has been established by medica Liberia and medica mondiale to connect providers of assistance from the healthcare, psychosocial and legal sectors. This ensures that comprehensive support can be rapidly provided to those affected.

In Sierra Leone, “Girls Clubs” offer girls a safe space where they can share their experiences of violence, their fears and also their hopes with each other. The meetings are also used to provide education on their bodies, sexual hygiene, and their rights. Where needed, they also receive psychosocial, legal or medical assistance.

Political women’s and human rights work

medica mondiale works actively in Germany and across the world, conducting political women’s and human rights work to promote equal participation of women in the shaping of their societies.

In this regard, the organisation appeals to governments to implement UN Resolution 1325. This international agreement from the year 2000 prescribes practical measures to prevent sexualised violence against women and increase their participation in peace negotiations.

In northern Iraq the women’s rights organisation EMMA campaigns actively to promote the political participation of women, ensure the rehabilitation of IS survivors and their children. They also conduct awareness-raising events for the general public.

In Southeast Europe medica mondiale supports the exchange of expertise and networking among women’s organisations in order to enhance their political and societal influence.